The Decline And Fall Of Flowtab, A Startup Story

It

started with an idea: How can we get our drinks more quickly at the

bar? Dreamed up at 2 a.m. in Coloft, a Los Angeles coworking space,

future founder Mike Townsend doodled up an iPad application mockup that he called Apptini to answer the question.

Apptini, a portmanteau of application and martini, wouldn’t last, but the product later known as Flowtab

had been born. Its life became a startup story that most don’t tell: A

company that didn’t make it. Technology as an industry worships success —

the bigger and splashier the better. What’s often left unsaid or swept

under the rug or buried under the guise of a micro acqui-hire is

failure. And lots of it.Young companies die by the hundreds in Silicon Valley, but you would hardly know it by reading your local blog. Flowtab, now a shuttered product, did something following its demise that I’ve never seen before — released a death chronicle of sorts. Their timeline and notes showcase the mistakes that the company made during its short life. Contracts, failed television appearances, deals that fell through, and more were published. If you work in technology, it’s a compelling set of documents.

I know Townsend, and have been in bars that at one point used Flowtab technology, so when the now former founders released their material, I caught up with both of them to talk through their history. What follows is the story of their dream, their company, struggle, failed pivots and an Australian mining magnate.

Beginnings

The pitch was simple: Flowtab would be a better way to order and pay for drinks. It would speed up service, as bartenders would no longer deal with payments, something that the software handled for the bar. No more bar tabs, no more lost or forgotten credit cards and IDs, or soggy receipts and dry pens. All that was replaced by an iPad behind the bar that displayed drink orders as they were logged by folks pecking on their smartphones. Customers then picked up their drinks when they were ready. Simple.

The idea was akin to a real-time GrubHub for the bar that you were currently sitting in. Flowtab would sport menus, and allow for tipping directly inside the app. Founders Townsend and Kyle Hill wanted to help you get your tipsy on.

Townsend took his iPad mockup and a short demo to 12 bars in the Santa Monica area, pitching a product that was utterly unbuilt. Response, Hill and Townsend recount, was good enough to keep moving on the project. Following the offline testing period, in mid-May of 2011, Flowtab put together a landing page. As Internet companies go, Flowtab had planted its flag. Two months later, the first version of Flowtab, coded in HTML5, was complete.

However, Flowtab was severely understaffed, and needed far more development firepower than it currently had in-house. Money was scarce, and Flowtab wanted someone truly top-notch. This created something of a problem. A friend of Hill’s had worked with a developer by the name of Alex Kouznetsov on an application in the past. Hill flew to see him in San Francisco. Kouznetsov, who has a Ph.D. in computer science and worked in Oakland at the time, started to contribute at nights and on weekends as the company’s CTO.

The first version of Flowtab was extremely limited. You could select the bar that you were in, pick a drink, set a tip amount, and hit order. But nothing more.

Eventually, Kouznetsov helped the Flowtab crew wrap their HTML5 up into a native shell (using Appcelerator), and get it into both the Android and iOS app stores. That launch, in February of 2012, proved premature, as Flowtab had zero bars using its technology for users to actually visit. Users of the application were therefore greeted with an empty app. Well, there were a few fake bars listed.

Ironically, Apple featured Flowtab for a week, sending it users that couldn’t actually use the app. At this stage, however, Flowtab remained focused more on talking to bar owners than acquiring users. The idea behind the focus was that, in the words of Townsend, “geographic density is absolutely key for any mobile payments application.”

That fact that Apple had noticed the app at all was good augur. The Flowtab boys were now ready to land some bars.

Bar Acquisition: Commence

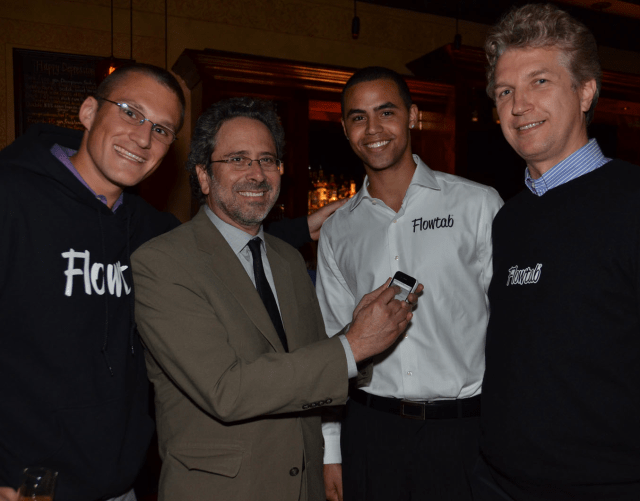

Flowtab held its coming out party at the Copa d’Oro bar in Santa Monica, processing around $1,200 in transactions throughout the evening. The mayor even showed up, and ordered a Coke using the app. Getting the mayor wasn’t easy for Townsend and Hill, who admitted to emailing him around 20 times, begging him to show up. It worked. Throughout the evening, customers placed 150 orders. It was a real, if moderate, success.

From left: Flowtab co-founder Mike Townsend, Santa Monica Mayor Richard Bloom, co-founder Kyle Hill and CTO Alex Kouznetsov

From left: Flowtab co-founder Mike Townsend, Santa Monica Mayor Richard Bloom, co-founder Kyle Hill and CTO Alex KouznetsovAfter the launch party, Flowtab was invited to present in the LA Startup Competition, an annual event. They won, besting 14 other startups, but turned down the offered investment from VoiVoida Ventures. The location of VoiVoida was far from Flowtab’s Santa Monica digs, and the company didn’t want to move. Still, the win felt good. Townsend called it a “confidence boost.”

Still in the learning stage of their venture, Team Flowtab went to the Nightclub and Bar Convention in Las Vegas. The company didn’t acquire new bar customers for its technology, but the trip did convince them that a business model idea that they were kicking around wouldn’t work: Flowtab could not be distributed through partnership with companies that sell Point of Sale (POS) systems.

Flowtab would therefore have to build its own sales team, it realized. That meant more overhead, more staff, and more work for the little company that remained dramatically under-capitalized.

By now, Flowtab had worked its way into three bars in L.A., but was seeing nothing like critical mass or organic growth. At its tender age and size, Flowtab had now decided that it needed intellectual property protection.

My IP Is My IP Not Your IP

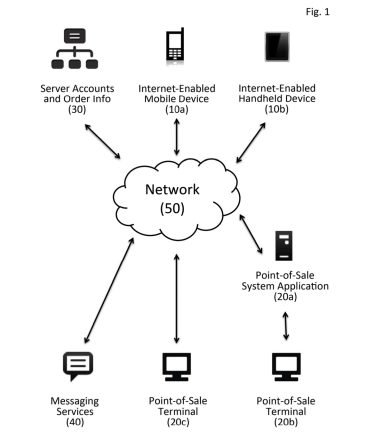

You want to protect your IP, right? Well, maybe not. Flowtab filed a patent concerning the “ability for merchant sellers and servers in hospitality establishments to use point-of-sale applications to send one-click/one-touch order-status notifications to mobile devices of their customers.” It wasn’t a good move.

Looking back, founders Hill and Townsend describe the effort as a waste of time, and a drain on their finances. It burned “lots of energy” and yielded nothing more than an “investor talking point,” they told me. Hill explained that the largest “value that [Flowtab] got out of the patent was convincing investors that it actually meant something.”

At this early stage in its corporate life, with only a few bars on its platform, and a user base in the hundreds, Flowtab spent and invested scarce resources into something that would eventually yield it nothing.

Better Apps, So Let’s Party Our Faces Off

Landing

July 1, 2012, the second version of Flowtab was done. Still coded in

HTML5 that was wrapped into native code, the second iteration was a

dramatic improvement on its predecessor. The bar-facing iPad app could

now load drink orders asynchronously, limiting meaningless refreshes.

The new version of Flowtab, like the two before it, was aimed more at

responding to bartender requests than answering users’ needs.With the new app in place, Flowtab wanted to bump up its usership figures, which meant that it planned another party. Flowtab wasn’t attracting many users on its own in the bars it was installed in, so it wanted to bring more to its locations, and do it in a very public fashion. The resulting event was a comical cockup.

Flowtab teamed up with Uber and Thrillist for the three-bar crawl. Each of the bars that Flowtab was installed in would be in play. Thrillist sold tickets, Uber ferried folks, and Flowtab was in charge of making sure that the drinks kept pouring.

“At this point,” said Hill, “we thought we were hot shit.” Three-hundred people were invited. The event was a catastrophe.

The app failed, the bars were understaffed, and drink orders piled up, leaving 35 in the queue at once in the second pub the group visited. That bar had a single bartender. It was stuffed with 150 patrons who were told that Flowtab could get them a drink, fast.

It’s great to go out and get your ass kicked.

Finally, Flowtab’s server went down, scuttling the entire operation. Hill started handing out margaritas by the fistful to keep everyone happy. The Flowtab team buckled under the stress. After the abortive bar bashes wound down, Hill went to the beach, wearing his Flowtab shirt, and sat down for an hour by himself. The app picked up a number of 1-star reviews following the debacle.Looking back, Hill and Townsend have a slightly positive take on the experience: It’s great to go out and get your ass kicked, they told me. Not that they would ever want to go through the agony of being in charge of hundreds of people wanting a drink as their server failed again, but it was like middle school: good to have done once. Hill claims that the situation provided “fuel” to keep going.

The event did lead to product improvements, including limiting the number of drinks that could be placed into the iPad app queue at a time. This cut bartender confusion, and helped staunch lines where people picked up their drinks. If the queue was full, you had to wait.

Another lesson: Sometimes you need to wade into new territory slowly, instead of cannonballing in, guns blazing, servers crashing.

Money

Flowtab now needed two things: money and guidance. After applying to a number of incubators in the L.A. area, Flowtab couldn’t find an open door. Local groups found it odd that their CTO was in the Bay Area and part time. Concerns were also raised about the size and approachability of the market that Flowtab had selected.

However, Mike Jones, the CEO of L.A.-based incubator and studio Science, helped the small company out by introducing it to DexOne, which sells advertising in the Yellow Pages. It’s a public firm, with a market capitalization of over $100 million. So, Flowtab linked up with the guys who print and leave massive phone books outside your apartment each year. DexOne has an experimental arm, which would prove important for Flowtab as it was a potential answer to its distribution question.

Technologists aren’t always salesman, but founders should be.

Around this time, Hill and Townsend went on Shark Tank, the reality TV investment program. In Hills’ words, it was a “long and drawn out process” that was “very involved.” The show wanted drama, and in the end not only did Flowtab not land a deal, but their pitch session didn’t make it onto TV, depriving the group of any free advertising they might have hoped for.After the accelerators didn’t bite, and Shark Tank had done little more than nibble, Flowtab decided to move north to San Francisco, where they hoped they would have more access to capital.

What about the bars in L.A.? Well, following the riotous bar crawl, they weren’t exactly enthused with the Flowtab product. The company cut loose, and following an endless wave of others, landed in the Bay Area.

The company raised $50,000 within the first month in the city.

DexOne: A Needed Friend

DexOne, the Yellow Pages company that sold nearly $2 billion of that product in 2012, was Flowtab’s shot at distribution. DexOne has a team of 12 that it partners with small tech companies to try out new things. Somewhat progressive, and perhaps interesting for a company so traditional, DexOne had what Flowtab did not: capital and manpower.

DexOne developed a pilot program to sell Flowtab in Colorado. It put six full-time sales people on the ground to push the new product. The partnership landed the largest strip club in Denver, Shotgun Willies, where the model worked moderately well. Culture, however, appeared to work against them. Folks in the strip club didn’t seem too excited about using their phones to order a drink.

The DexOne deal landed a few other bars, as well, but as in L.A., the growth was slow, and only garnered by firm grind. Back in San Francisco, the Flowtab team was experimenting with new ways to grab bars, and hopefully, paying customers.

San Francisco

Crowdsourcing might be a dead buzzword, but hiring out grunt work is as popular as ever. Flowtab, in a bid to reach more bars, hired a call center in the Philippines to call potential bars in San Francisco. The idea was to massively scale their initial outreach, and then send in the founders to lock down deals that the call center would set up for them.

The lesson according to Flowtab: Technologists aren’t always salesman, but founders should be.

After the call center didn’t perform, Flowtab hired Trevor Bisset, who promptly cut the call center on his first day on the job. Weeks later, he had landed the group’s first bar in the city, McTeague’s.

A short note on McTeague’s. The bar is located on Polk Street here in San Francisco. It’s a fine place to be Monday through Thursday, a low-key sports bar that won’t be too crowded unless the Giants are on a streak. But Fridays and weekends at McTeague’s are a complete zoo. Amateurs from four counties descend on the place, turning it into a part club, part bar, and complete goat rodeo. You can’t get to the bar, let alone get a drink.

So, if there were ever a bar that Flowtab should work at, it was McTeague’s. Anything to break the logjam would be welcome. McTeague’s remains the only bar in San Francisco to my knowledge that has a sign in the bathroom stating that drug use is not allowed, and that bar staff will be checking to ensure that things remain clean. People still do coke, presumably, but the place would prefer it if they didn’t.

McTeague’s was a get for Flowtab, but they had eyes on a bigger prize: the San Francisco Marriott Marquis. With 1,500 rooms, it’s massive. It has three bars. Landing the hotel would have been a coup. The team designed and pitched a presentation. But in the end, Flowtab’s lack of feature capability to integrate with the Marquis’s point of sale system (Micros) scuttled the idea.

Startups are human endeavors, and around this time, a friend of the company, Brandon Zacharie, started contributing for beer and pizza. The team credits Zacharie with getting them off FTP and onto Git where they belonged. According to Hill, Zacharie specifically helped the team “integrate web socket connection between the user app and the [bar’s] iPad” application.

Meanwhile In Denver

Three bars locked down but not doing much in San Francisco, the DexOne work in Colorado was ramping up. Little Flowtab found itself a bit more stretched than it could manage. The team would later liken the moment to tossing logs onto a small fire, choking it.

Flowtab wasn’t performing well in the bars close to its core team. How could DexOne flog the product successfully? Despite the fact that people were not organically flocking to the app in bars, DexOne wanted to press ahead and get Flowtab into even more locations. A doubling-down in Denver? Yes. Orlando? DexOne wanted to go there. Portland? Yeah.

But Flowtab, far away from the Rockies, didn’t have enough money to support that many cities, and had concerns about its business model, which at that point charged users $1 to file an order.

The handful of bars that were signed up in Denver through the DexOne deal paid $1,200 to get started with Flowtab. It wasn’t a small sum, but the cash went to providing them with the hardware that they needed to run the service (an iPad, etc.).

Worried about money and consumer reaction to the product in its current form, Flowtab declined the expansion that DexOne wanted.

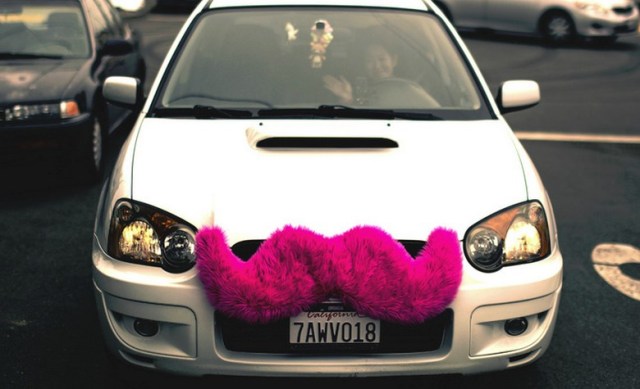

Lyft

Ironically, one of the most successful efforts that Flowtab found to accumulate new users was killed by the ridesharing service Lyft. Don’t fret, Lyft had every right to do so. Flowtab recruited Lyft drivers to hand out free drink coupons to riders heading to bars that it was installed in. Drivers got $5 every time a rider signed up and ordered, and that drink was free for the new user. Around 30 drivers took part, and more than 1,000 drinks were given away.

Ask forgiveness, not permission was the idea here. It worked until it didn’t, and it didn’t when Lyft asked them politely to knock it off. Still, for three months Flowtab was picking up new users at a decent pace, a rare moment of encouraging growth for the company.

Empty Distribution

With a fresh $25,000 note from a technology investor at a venture capital group in Palo Alto, Flowtab had 12 active bars in three cities by January 2013 but little in the way of active users. The company set a small goal: By March 1, they wanted to have at least 50 active users, who were using Flowtab several times per month.

As a company, Flowtab was beleaguered by inconsistent usage; most folks just didn’t go back to the same bar every week, so a new user might enjoy Flowtab, but not use the service again for months until they were back in the bar they signed up in.

Order volume was low, and as a company Flowtab was starting to doubt its model. Were they only able to pick up new users through gimmicks? Would they always have to show up to a bar to get people to sign up? Order volume could spike over 60 orders in a day if Flowtab had a presence at a bar. But when they weren’t it would fall, sometimes to single digits.

It was time to prove that Flowtab could scale. With 12 bars, the company had enough market presence to test its service. It would get users to the bars, and then see if it could keep them around. Hill and Townsend came up with 12 new ways to get users, including Facebook ads. Each effort, according to Hill, “fell flat on its face.” Nothing spurred organic growth, and Flowtab didn’t have the funds to keep buying users that were at best infrequent revenue sources.

As a final effort to see what could be done, Flowtab decided to have a much smaller party. McTeague’s and the nearby Mayes were pressed into service for the Super Bowl-themed event. About 100 attendees floated between the two bars. Unlike the L.A. pub crawl meltdown, the event cost Flowtab a modest $500.

They acquired 92 new users, which worked out to around $5.50 per. That was cheaper than the Lyft effort, which cost $5 for the drivers plus a drink for the new user.

The economics were difficult to make work. Flowtab’s $1-per-order fee meant that even at $5.50 per new account, the average user would have to make six orders in the history of their usership to allow Flowtab to break even. People were not drinking enough to make that feasible.

More Money And A New Business Model

The DexOne partnership had proven that some bars were willing to pay for Flowtab, but a few checks of $1,200 apiece were not going to float the company. Flowtab wanted to raise $300,000, but in the face of its challenges, the sum was daunting.

And with its current business model floundering, Flowtab decided it was time to pivot. So, instead of charging users to pay an extra fee to use its service, Flowtab flipped around and decided to sell advertising to alcohol companies inside of its application. About to order whiskey? Why not a Jim Beam?

It made some sense: Bars and users were not rich, but the corporate interests behind Bacardi and Johnnie Walker certainly were. And they are banned from advertising inside of a bar.

Flowtab felt that since it was a mobile application, the law did not apply to them. However, after meeting with six small and large liquor and beer companies, it became clear that Flowtab simply did not have the scale needed to land a deal large enough to matter.

Alcohol Apocalypse

February 2013 was a brutal month for the other small companies looking to execute something similar to Flowtab. BarTab, which had raised more than $1.5 million, essentially went offline. Coaster, a local competitor, in the words of Flowtab, “began losing bars.”

The shakeup of its better-funded rivals unnerved Flowtab: If folks with more money and distribution than themselves couldn’t make the model work, what shot did they have?

It was stock-taking time. Flowtab had, in its own estimation, zero organic growth and few if any regular users, and it couldn’t find a conduit to new users that would scale. New efforts would cause a minor rise that would anti-soufflé the moment the monetary influx halted.

Six weeks into the process, and given its doubts about its model, Flowtab put fundraising on ice. They had $20,000 left in the bank, and its hopes to pull off its bar model were tanking.

It was time for another pivot.

Pivot 2.0

It’s now March 2013. Flowtab had burned through a total of $110,000. It had fewer than 2,000 users, and the team had come to the conclusion that they did not have product-market fit. I suspect the team could have come to this conclusion far sooner if they knew a year prior what they knew in March.

In the end, the team decided that their problem was distance. GrubHub, which is comically successful, brings something to you that is far from you. Flowtab wasn’t saving you enough time or energy to make it a compelling experience.

However, the team had built a technology stack and had a few dollars left in the bank. They began looking for a new application for their software. After poking around golf courses, hotels, and other potential venues, Flowtab decided that stadiums were the best bet for its tech. Beer as a Service? Something like that.

In startup style, Hill and Townsend called every stadium in California — there are 114 if you were wondering — and met face to face with a few, including the Giants, Warriors, and A’s. However, even as they were starting to sour on the prospect of stadiums (too much regulation and other issues), a different company called Bypass raised $3.5 million, partially from AEG, which manages 50 stadiums. eBay-owned StubHub also took part in the raise.

If there had been a slightly open door to apply Flowtab to the stadium business, it had closed.

Flowtab was “just like……… fuck” at that point, according to its founders.

Mike Jones, Final Round

Mike Jones of Science, who had helped Flowtab land the DexOne deal, met with the company again. The team needed counsel. After explaining their stadium exploits, Jones agreed that it didn’t make sense as an avenue for the firm. The company was also all but flat broke.

“The last two years have been a huge learning experience, and we believe the real failure would be not sharing our story with the world.”

Seven days after Bypass’s raise was announced, on April 17, Flowtab was shuttered. Trevor the sales guy went to a startup in Portland. Friend of the company Zacharie went full time at a different startup, and the erstwhile CTO kept to his day job.Jones offered to hire Hill and Townsend into Science — it was a non-monetary acquisition of sorts — where they worked on and recently launched HomeHero, a marketplace for home care of seniors.

As part of the Science deal, both Hill and Townsend are back in Los Angeles, full circle from where they started. It was a long, eventful, often ridiculous, and always stressful experience. But to hear the founders tell it, it was a rollercoaster, but one that had them grinning through nearly all of its twists and turns.

Post Script: The Australian Mining Magnate

The oddest piece of Flowtab history started with a random email that was almost deleted. A dude in Australia loved the product and the idea and wanted to chat. This was in February 2013.

The Aussie, who had made his money in mining, liked Flowtab enough to fly out to meet the fledgling firm. Three months later, a month after the company had been shuttered and the team scattered, an acquisition offer was made.

But with new roles at Science, and no team to speak of, they turned it down. Flowtab was no more. “In the end, Flowtab failed in the sense that we never IPO’d or sold the company,” Hill concluded. “But the last two years have been a huge learning experience, and we believe the real failure would be not sharing our story with the world.”

Read, examine their documents, and do not repeat their mistakes.